NNabla Python API Demonstration Tutorial¶

Let us import nnabla first, and some additional useful tools.

# python2/3 compatibility

from __future__ import print_function

from __future__ import absolute_import

from __future__ import division

import nnabla as nn # Abbreviate as nn for convenience.

import numpy as np

%matplotlib inline

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

2017-09-27 14:00:30,785 [nnabla][INFO]: Initializing CPU extension...

NdArray¶

NdArray is a data container of a multi-dimensional array. NdArray is

device (e.g. CPU, CUDA) and type (e.g. uint8, float32) agnostic, in

which both type and device are implicitly casted or transferred when it

is used. Below, you create a NdArray with a shape of (2, 3, 4).

a = nn.NdArray((2, 3, 4))

You can see the values held inside a by the following. The values

are not initialized, and are created as float32 by default.

print(a.data)

[[[ 9.42546995e+24 4.56809286e-41 8.47690058e-38 0.00000000e+00]

[ 7.38056336e+34 7.50334969e+28 1.17078231e-32 7.58387310e+31]

[ 7.87001454e-12 9.84394250e-12 6.85712044e+22 1.81785692e+31]]

[[ 1.84681296e+25 1.84933247e+20 4.85656319e+33 2.06176836e-19]

[ 6.80020530e+22 1.69307638e+22 2.11235872e-19 1.94316151e-19]

[ 1.81805047e+31 3.01289097e+29 2.07004908e-19 1.84648795e+25]]]

The accessor .data returns a reference to the values of NdArray as

numpy.ndarray. You can modify these by using the NumPy API as

follows.

print('[Substituting random values]')

a.data = np.random.randn(*a.shape)

print(a.data)

print('[Slicing]')

a.data[0, :, ::2] = 0

print(a.data)

[Substituting random values]

[[[ 0.36133638 0.22121875 -1.5912329 -0.33490974]

[ 1.35962474 0.2165522 0.54483992 -0.61813235]

[-0.13718799 -0.44104072 -0.51307833 0.73900551]]

[[-0.59464753 -2.17738533 -0.28626776 -0.45654735]

[ 0.73566747 0.87292582 -0.41605178 0.04792296]

[-0.63856047 0.31966645 -0.63974309 -0.61385244]]]

[Slicing]

[[[ 0. 0.22121875 0. -0.33490974]

[ 0. 0.2165522 0. -0.61813235]

[ 0. -0.44104072 0. 0.73900551]]

[[-0.59464753 -2.17738533 -0.28626776 -0.45654735]

[ 0.73566747 0.87292582 -0.41605178 0.04792296]

[-0.63856047 0.31966645 -0.63974309 -0.61385244]]]

Note that the above operation is all done in the host device (CPU).

NdArray provides more efficient functions in case you want to fill all

values with a constant, .zero and .fill. They are lazily

evaluated when the data is requested (when neural network computation

requests the data, or when NumPy array is requested by Python) The

filling operation is executed within a specific device (e.g. CUDA GPU),

and more efficient if you specify the device setting, which we explain

later.

a.fill(1) # Filling all values with one.

print(a.data)

[[[ 1. 1. 1. 1.]

[ 1. 1. 1. 1.]

[ 1. 1. 1. 1.]]

[[ 1. 1. 1. 1.]

[ 1. 1. 1. 1.]

[ 1. 1. 1. 1.]]]

You can create an NdArray instance directly from a NumPy array object.

b = nn.NdArray.from_numpy_array(np.ones(a.shape))

print(b.data)

[[[ 1. 1. 1. 1.]

[ 1. 1. 1. 1.]

[ 1. 1. 1. 1.]]

[[ 1. 1. 1. 1.]

[ 1. 1. 1. 1.]

[ 1. 1. 1. 1.]]]

NdArray is used in Variable class, as well as NNabla’s imperative computation of neural networks. We describe them in the later sections.

Variable¶

Variable class is used when you construct a neural network. The neural network can be described as a graph in which an edge represents a function (a.k.a operator and layer) which defines operation of a minimum unit of computation, and a node represents a variable which holds input/output values of a function (Function class is explained later). The graph is called “Computation Graph”.

In NNabla, a Variable, a node of a computation graph, holds two

NdArrays, one for storing the input or output values of a function

during forward propagation (executing computation graph in the forward

order), while another for storing the backward error signal (gradient)

during backward propagation (executing computation graph in backward

order to propagate error signals down to parameters (weights) of neural

networks). The first one is called data, the second is grad in

NNabla.

The following line creates a Variable instance with a shape of (2, 3,

4). It has data and grad as NdArray. The flag need_grad

is used to omit unnecessary gradient computation during backprop if set

to False.

x = nn.Variable([2, 3, 4], need_grad=True)

print('x.data:', x.data)

print('x.grad:', x.grad)

x.data: <NdArray((2, 3, 4)) at 0x7f575caf4ea0>

x.grad: <NdArray((2, 3, 4)) at 0x7f575caf4ea0>

You can get the shape by:

x.shape

(2, 3, 4)

Since both data and grad are NdArray, you can get a

reference to its values as NdArray with the .data accessor, but also

it can be referred by .d or .g property for data and grad

respectively.

print('x.data')

print(x.d)

x.d = 1.2345 # To avoid NaN

assert np.all(x.d == x.data.data), 'd: {} != {}'.format(x.d, x.data.data)

print('x.grad')

print(x.g)

x.g = 1.2345 # To avoid NaN

assert np.all(x.g == x.grad.data), 'g: {} != {}'.format(x.g, x.grad.data)

# Zeroing grad values

x.grad.zero()

print('x.grad (after `.zero()`)')

print(x.g)

x.data

[[[ 9.42553452e+24 4.56809286e-41 8.32543479e-38 0.00000000e+00]

[ nan nan 0.00000000e+00 0.00000000e+00]

[ 3.70977305e+25 4.56809286e-41 3.78350585e-44 0.00000000e+00]]

[[ 5.68736600e-38 0.00000000e+00 1.86176378e-13 4.56809286e-41]

[ 4.74367616e+25 4.56809286e-41 5.43829710e+19 4.56809286e-41]

[ 0.00000000e+00 0.00000000e+00 2.93623372e-38 0.00000000e+00]]]

x.grad

[[[ 9.42576510e+24 4.56809286e-41 9.42576510e+24 4.56809286e-41]

[ 9.27127763e-38 0.00000000e+00 9.27127763e-38 0.00000000e+00]

[ 1.69275966e+22 4.80112800e+30 1.21230330e+25 7.22962302e+31]]

[[ 1.10471027e-32 4.63080422e+27 2.44632805e+20 2.87606258e+20]

[ 4.46263300e+30 4.62311881e+30 7.65000750e+28 3.01339003e+29]

[ 2.08627352e-10 1.03961868e+21 7.99576678e+20 1.74441223e+22]]]

x.grad (after .zero())

[[[ 0. 0. 0. 0.]

[ 0. 0. 0. 0.]

[ 0. 0. 0. 0.]]

[[ 0. 0. 0. 0.]

[ 0. 0. 0. 0.]

[ 0. 0. 0. 0.]]]

Like NdArray, a Variable can also be created from NumPy

array(s).

x2 = nn.Variable.from_numpy_array(np.ones((3,)), need_grad=True)

print(x2)

print(x2.d)

x3 = nn.Variable.from_numpy_array(np.ones((3,)), np.zeros((3,)), need_grad=True)

print(x3)

print(x3.d)

print(x3.g)

<Variable((3,), need_grad=True) at 0x7f572a5242c8>

[ 1. 1. 1.]

<Variable((3,), need_grad=True) at 0x7f572a5244a8>

[ 1. 1. 1.]

[ 0. 0. 0.]

Besides storing values of a computation graph, pointing a parent edge

(function) to trace the computation graph is an important role. Here

x doesn’t have any connection. Therefore, the .parent property

returns None.

print(x.parent)

None

Function¶

A function defines an operation block of a computation graph as we

described above. The module nnabla.functions offers various

functions (e.g. Convolution, Affine and ReLU). You can see the list of

functions available in the API reference

guide.

import nnabla.functions as F

As an example, here you will defines a computation graph that computes the element-wise Sigmoid function outputs for the input variable and sums up all values into a scalar. (This is simple enough to explain how it behaves but a meaningless example in the context of neural network training. We will show you a neural network example later.)

sigmoid_output = F.sigmoid(x)

sum_output = F.reduce_sum(sigmoid_output)

The function API in nnabla.functions takes one (or several)

Variable(s) and arguments (if any), and returns one (or several) output

Variable(s). The .parent points to the function instance which

created it. Note that no computation occurs at this time since we just

define the graph. (This is the default behavior of NNabla computation

graph API. You can also fire actual computation during graph definition

which we call “Dynamic mode” (explained later)).

print("sigmoid_output.parent.name:", sigmoid_output.parent.name)

print("x:", x)

print("sigmoid_output.parent.inputs refers to x:", sigmoid_output.parent.inputs)

sigmoid_output.parent.name: Sigmoid

x: <Variable((2, 3, 4), need_grad=True) at 0x7f572a51a778>

sigmoid_output.parent.inputs refers to x: [<Variable((2, 3, 4), need_grad=True) at 0x7f572a273a48>]

print("sum_output.parent.name:", sum_output.parent.name)

print("sigmoid_output:", sigmoid_output)

print("sum_output.parent.inputs refers to sigmoid_output:", sum_output.parent.inputs)

sum_output.parent.name: ReduceSum

sigmoid_output: <Variable((2, 3, 4), need_grad=True) at 0x7f572a524638>

sum_output.parent.inputs refers to sigmoid_output: [<Variable((2, 3, 4), need_grad=True) at 0x7f572a273a48>]

The .forward() at a leaf Variable executes the forward pass

computation in the computation graph.

sum_output.forward()

print("CG output:", sum_output.d)

print("Reference:", np.sum(1.0 / (1.0 + np.exp(-x.d))))

CG output: 18.59052085876465

Reference: 18.5905

The .backward() does the backward propagation through the graph.

Here we initialize the grad values as zero before backprop since the

NNabla backprop algorithm always accumulates the gradient in the root

variables.

x.grad.zero()

sum_output.backward()

print("d sum_o / d sigmoid_o:")

print(sigmoid_output.g)

print("d sum_o / d x:")

print(x.g)

d sum_o / d sigmoid_o:

[[[ 1. 1. 1. 1.]

[ 1. 1. 1. 1.]

[ 1. 1. 1. 1.]]

[[ 1. 1. 1. 1.]

[ 1. 1. 1. 1.]

[ 1. 1. 1. 1.]]]

d sum_o / d x:

[[[ 0.17459197 0.17459197 0.17459197 0.17459197]

[ 0.17459197 0.17459197 0.17459197 0.17459197]

[ 0.17459197 0.17459197 0.17459197 0.17459197]]

[[ 0.17459197 0.17459197 0.17459197 0.17459197]

[ 0.17459197 0.17459197 0.17459197 0.17459197]

[ 0.17459197 0.17459197 0.17459197 0.17459197]]]

NNabla is developed by mainly focused on neural network training and

inference. Neural networks have parameters to be learned associated with

computation blocks such as Convolution, Affine (a.k.a. fully connected,

dense etc.). In NNabla, the learnable parameters are also represented as

Variable objects. Just like input variables, those parameter

variables are also used by passing into Functions. For example,

Affine function takes input, weights and biases as inputs.

x = nn.Variable([5, 2]) # Input

w = nn.Variable([2, 3], need_grad=True) # Weights

b = nn.Variable([3], need_grad=True) # Biases

affine_out = F.affine(x, w, b) # Create a graph including only affine

The above example takes an input with B=5 (batchsize) and D=2 (dimensions) and maps it to D’=3 outputs, i.e. (B, D’) output.

You may also notice that here you set need_grad=True only for

parameter variables (w and b). The x is a non-parameter variable and the

root of computation graph. Therefore, it doesn’t require gradient

computation. In this configuration, the gradient computation for x is

not executed in the first affine, which will omit the computation of

unnecessary backpropagation.

The next block sets data and initializes grad, then applies forward and backward computation.

# Set random input and parameters

x.d = np.random.randn(*x.shape)

w.d = np.random.randn(*w.shape)

b.d = np.random.randn(*b.shape)

# Initialize grad

x.grad.zero() # Just for showing gradients are not computed when need_grad=False (default).

w.grad.zero()

b.grad.zero()

# Forward and backward

affine_out.forward()

affine_out.backward()

# Note: Calling backward at non-scalar Variable propagates 1 as error message from all element of outputs. .

You can see that affine_out holds an output of Affine.

print('F.affine')

print(affine_out.d)

print('Reference')

print(np.dot(x.d, w.d) + b.d)

F.affine

[[-0.17701732 2.86095762 -0.82298267]

[-0.75544345 -1.16702223 -2.44841242]

[-0.36278027 -3.4771595 -0.75681627]

[ 0.32743117 0.24258983 1.30944324]

[-0.87201929 1.94556415 -3.23357344]]

Reference

[[-0.1770173 2.86095762 -0.82298267]

[-0.75544345 -1.16702223 -2.44841242]

[-0.3627803 -3.4771595 -0.75681627]

[ 0.32743117 0.24258983 1.309443 ]

[-0.87201929 1.94556415 -3.23357344]]

The resulting gradients of weights and biases are as follows.

print("dw")

print(w.g)

print("db")

print(b.g)

dw

[[ 3.10820675 3.10820675 3.10820675]

[ 0.37446201 0.37446201 0.37446201]]

db

[ 5. 5. 5.]

The gradient of x is not changed because need_grad is set as

False.

print(x.g)

[[ 0. 0.]

[ 0. 0.]

[ 0. 0.]

[ 0. 0.]

[ 0. 0.]]

Parametric Function¶

Considering parameters as inputs of Function enhances expressiveness

and flexibility of computation graphs. However, to define all parameters

for each learnable function is annoying for users to define a neural

network. In NNabla, trainable models are usually created by composing

functions that have optimizable parameters. These functions are called

“Parametric Functions”. The Parametric Function API provides various

parametric functions and an interface for composing trainable models.

To use parametric functions, import:

import nnabla.parametric_functions as PF

The function with optimizable parameter can be created as below.

with nn.parameter_scope("affine1"):

c1 = PF.affine(x, 3)

The first line creates a parameter scope. The second line then

applies PF.affine - an affine transform - to x, and creates a

variable c1 holding that result. The parameters are created and

initialized randomly at function call, and registered by a name

“affine1” using parameter_scope context. The function

nnabla.get_parameters() allows to get the registered parameters.

nn.get_parameters()

OrderedDict([('affine1/affine/W',

<Variable((2, 3), need_grad=True) at 0x7f572822f0e8>),

('affine1/affine/b',

<Variable((3,), need_grad=True) at 0x7f572822f138>)])

The name= argument of any PF function creates the equivalent

parameter space to the above definition of PF.affine transformation

as below. It could save the space of your Python code. The

nnabla.parametric_scope is more useful when you group multiple

parametric functions such as Convolution-BatchNormalization found in a

typical unit of CNNs.

c1 = PF.affine(x, 3, name='affine1')

nn.get_parameters()

OrderedDict([('affine1/affine/W',

<Variable((2, 3), need_grad=True) at 0x7f572822f0e8>),

('affine1/affine/b',

<Variable((3,), need_grad=True) at 0x7f572822f138>)])

It is worth noting that the shapes of both outputs and parameter variables (as you can see above) are automatically determined by only providing the output size of affine transformation(in the example above the output size is 3). This helps to create a graph in an easy way.

c1.shape

(5, 3)

Parameter scope can be nested as follows (although a meaningless example).

with nn.parameter_scope('foo'):

h = PF.affine(x, 3)

with nn.parameter_scope('bar'):

h = PF.affine(h, 4)

This creates the following.

nn.get_parameters()

OrderedDict([('affine1/affine/W',

<Variable((2, 3), need_grad=True) at 0x7f572822f0e8>),

('affine1/affine/b',

<Variable((3,), need_grad=True) at 0x7f572822f138>),

('foo/affine/W',

<Variable((2, 3), need_grad=True) at 0x7f572822fa98>),

('foo/affine/b',

<Variable((3,), need_grad=True) at 0x7f572822fae8>),

('foo/bar/affine/W',

<Variable((3, 4), need_grad=True) at 0x7f572822f728>),

('foo/bar/affine/b',

<Variable((4,), need_grad=True) at 0x7f572822fdb8>)])

Also, get_parameters() can be used in parameter_scope. For

example:

with nn.parameter_scope("foo"):

print(nn.get_parameters())

OrderedDict([('affine/W', <Variable((2, 3), need_grad=True) at 0x7f572822fa98>), ('affine/b', <Variable((3,), need_grad=True) at 0x7f572822fae8>), ('bar/affine/W', <Variable((3, 4), need_grad=True) at 0x7f572822f728>), ('bar/affine/b', <Variable((4,), need_grad=True) at 0x7f572822fdb8>)])

nnabla.clear_parameters() can be used to delete registered

parameters under the scope.

with nn.parameter_scope("foo"):

nn.clear_parameters()

print(nn.get_parameters())

OrderedDict([('affine1/affine/W', <Variable((2, 3), need_grad=True) at 0x7f572822f0e8>), ('affine1/affine/b', <Variable((3,), need_grad=True) at 0x7f572822f138>)])

MLP Example For Explanation¶

The following block creates a computation graph to predict one dimensional output from two dimensional inputs by a 2 layer fully connected neural network (multi-layer perceptron).

nn.clear_parameters()

batchsize = 16

x = nn.Variable([batchsize, 2])

with nn.parameter_scope("fc1"):

h = F.tanh(PF.affine(x, 512))

with nn.parameter_scope("fc2"):

y = PF.affine(h, 1)

print("Shapes:", h.shape, y.shape)

Shapes: (16, 512) (16, 1)

This will create the following parameter variables.

nn.get_parameters()

OrderedDict([('fc1/affine/W',

<Variable((2, 512), need_grad=True) at 0x7f572822fef8>),

('fc1/affine/b',

<Variable((512,), need_grad=True) at 0x7f572822f9a8>),

('fc2/affine/W',

<Variable((512, 1), need_grad=True) at 0x7f572822f778>),

('fc2/affine/b',

<Variable((1,), need_grad=True) at 0x7f572822ff98>)])

As described above, you can execute the forward pass by calling forward method at the terminal variable.

x.d = np.random.randn(*x.shape) # Set random input

y.forward()

print(y.d)

[[-0.05708594]

[ 0.01661986]

[-0.34168088]

[ 0.05822293]

[-0.16566885]

[-0.04867431]

[ 0.2633169 ]

[ 0.10496549]

[-0.01291842]

[-0.09726256]

[-0.05720493]

[-0.09691752]

[-0.07822668]

[-0.17180404]

[ 0.11970415]

[-0.08222144]]

Training a neural networks needs a loss value to be minimized by gradient descent with backprop. In NNabla, loss function is also a just function, and packaged in the functions module.

# Variable for label

label = nn.Variable([batchsize, 1])

# Set loss

loss = F.reduce_mean(F.squared_error(y, label))

# Execute forward pass.

label.d = np.random.randn(*label.shape) # Randomly generate labels

loss.forward()

print(loss.d)

1.9382084608078003

As you’ve seen above, NNabla backward accumulates the gradients at

the root variables. You have to initialize the grad of the parameter

variables before backprop (We will show you the easiest way with

Solver API).

# Collect all parameter variables and init grad.

for name, param in nn.get_parameters().items():

param.grad.zero()

# Gradients are accumulated to grad of params.

loss.backward()

Imperative Mode¶

After performing backprop, gradients are held in parameter variable grads. The next block will update the parameters with vanilla gradient descent.

for name, param in nn.get_parameters().items():

param.data -= param.grad * 0.001 # 0.001 as learning rate

The above computation is an example of NNabla’s “Imperative Mode” for

executing neural networks. Normally, NNabla functions (instances of

nnabla.functions)

take Variables as their input. When at least one NdArray is

provided as an input for NNabla functions (instead of Variables),

the function computation will be fired immediately, and returns an

NdArray as the output, instead of returning a Variable. In the

above example, the NNabla functions F.mul_scalar and F.sub2 are

called by the overridden operators * and -=, respectively.

In other words, NNabla’s “Imperative mode” doesn’t create a computation graph, and can be used like NumPy. If device acceleration such as CUDA is enabled, it can be used like NumPy empowered with device acceleration. Parametric functions can also be used with NdArray input(s). The following block demonstrates a simple imperative execution example.

# A simple example of imperative mode.

xi = nn.NdArray.from_numpy_array(np.arange(4).reshape(2, 2))

yi = F.relu(xi - 1)

print(xi.data)

print(yi.data)

[[0 1]

[2 3]]

[[ 0. 0.]

[ 1. 2.]]

Note that in-place substitution from the rhs to the lhs cannot be done

by the = operator. For example, when x is an NdArray,

writing x = x + 1 will not increment all values of x -

instead, the expression on the rhs will create a new NdArray

object that is different from the one originally bound by x, and binds

the new NdArray object to the Python variable x on the lhs.

For in-place editing of NdArrays, the in-place assignment operators

+=, -=, *=, and /= can be used. The copy_from method

can also be used to copy values of an existing NdArray to another.

For example, incrementing 1 to x, an NdArray, can be done by

x.copy_from(x+1). The copy is performed with device acceleration if

a device context is specified by using nnabla.set_default_context or

nnabla.context_scope.

# The following doesn't perform substitution but assigns a new NdArray object to `xi`.

# xi = xi + 1

# The following copies the result of `xi + 1` to `xi`.

xi.copy_from(xi + 1)

assert np.all(xi.data == (np.arange(4).reshape(2, 2) + 1))

# Inplace operations like `+=`, `*=` can also be used (more efficient).

xi += 1

assert np.all(xi.data == (np.arange(4).reshape(2, 2) + 2))

Solver¶

NNabla provides stochastic gradient descent algorithms to optimize

parameters listed in the nnabla.solvers module. The parameter

updates demonstrated above can be replaced with this Solver API, which

is easier and usually faster.

from nnabla import solvers as S

solver = S.Sgd(lr=0.00001)

solver.set_parameters(nn.get_parameters())

# Set random data

x.d = np.random.randn(*x.shape)

label.d = np.random.randn(*label.shape)

# Forward

loss.forward()

Just call the the following solver method to fill zero grad region, then backprop

solver.zero_grad()

loss.backward()

The following block updates parameters with the Vanilla Sgd rule (equivalent to the imperative example above).

solver.update()

Toy Problem To Demonstrate Training¶

The following function defines a regression problem which computes the norm of a vector.

def vector2length(x):

# x : [B, 2] where B is number of samples.

return np.sqrt(np.sum(x ** 2, axis=1, keepdims=True))

We visualize this mapping with the contour plot by matplotlib as follows.

# Data for plotting contour on a grid data.

xs = np.linspace(-1, 1, 100)

ys = np.linspace(-1, 1, 100)

grid = np.meshgrid(xs, ys)

X = grid[0].flatten()

Y = grid[1].flatten()

def plot_true():

"""Plotting contour of true mapping from a grid data created above."""

plt.contourf(xs, ys, vector2length(np.hstack([X[:, None], Y[:, None]])).reshape(100, 100))

plt.axis('equal')

plt.colorbar()

plot_true()

We define a deep prediction neural network.

def length_mlp(x):

h = x

for i, hnum in enumerate([4, 8, 4, 2]):

h = F.tanh(PF.affine(h, hnum, name="fc{}".format(i)))

y = PF.affine(h, 1, name='fc')

return y

nn.clear_parameters()

batchsize = 100

x = nn.Variable([batchsize, 2])

y = length_mlp(x)

label = nn.Variable([batchsize, 1])

loss = F.reduce_mean(F.squared_error(y, label))

We created a 5 layers deep MLP using for-loop. Note that only 3 lines of the code potentially create infinitely deep neural networks. The next block adds helper functions to visualize the learned function.

def predict(inp):

ret = []

for i in range(0, inp.shape[0], x.shape[0]):

xx = inp[i:i + x.shape[0]]

# Imperative execution

xi = nn.NdArray.from_numpy_array(xx)

yi = length_mlp(xi)

ret.append(yi.data.copy())

return np.vstack(ret)

def plot_prediction():

plt.contourf(xs, ys, predict(np.hstack([X[:, None], Y[:, None]])).reshape(100, 100))

plt.colorbar()

plt.axis('equal')

Next we instantiate a solver object as follows. We use Adam optimizer which is one of the most popular SGD algorithm used in the literature.

from nnabla import solvers as S

solver = S.Adam(alpha=0.01)

solver.set_parameters(nn.get_parameters())

The following function generates data from the true system infinitely.

def random_data_provider(n):

x = np.random.uniform(-1, 1, size=(n, 2))

y = vector2length(x)

return x, y

In the next block, we run 2000 training steps (SGD updates).

num_iter = 2000

for i in range(num_iter):

# Sample data and set them to input variables of training.

xx, ll = random_data_provider(batchsize)

x.d = xx

label.d = ll

# Forward propagation given inputs.

loss.forward(clear_no_need_grad=True)

# Parameter gradients initialization and gradients computation by backprop.

solver.zero_grad()

loss.backward(clear_buffer=True)

# Apply weight decay and update by Adam rule.

solver.weight_decay(1e-6)

solver.update()

# Just print progress.

if i % 100 == 0 or i == num_iter - 1:

print("Loss@{:4d}: {}".format(i, loss.d))

Loss@ 0: 0.6976373195648193

Loss@ 100: 0.08075223118066788

Loss@ 200: 0.005213144235312939

Loss@ 300: 0.001955194864422083

Loss@ 400: 0.0011660841992124915

Loss@ 500: 0.0006421314901672304

Loss@ 600: 0.0009330055327154696

Loss@ 700: 0.0008817618945613503

Loss@ 800: 0.0006205961108207703

Loss@ 900: 0.0009072928223758936

Loss@1000: 0.0008160348515957594

Loss@1100: 0.0011569359339773655

Loss@1200: 0.000837412488181144

Loss@1300: 0.0011542742140591145

Loss@1400: 0.0005833200993947685

Loss@1500: 0.0009848927147686481

Loss@1600: 0.0005141657311469316

Loss@1700: 0.0009339841199107468

Loss@1800: 0.000950580753851682

Loss@1900: 0.0005430278833955526

Loss@1999: 0.0007046313839964569

Memory usage optimization: You may notice that, in the above

updates, .forward() is called with the clear_no_need_grad=

option, and .backward() is called with the clear_buffer= option.

Training of neural network in more realistic scenarios usually consumes

huge memory due to the nature of backpropagation algorithm, in which all

of the forward variable buffer data should be kept in order to

compute the gradient of a function. In a naive implementation, we keep

all the variable data and grad living until the NdArray

objects are not referenced (i.e. the graph is deleted). The clear_*

options in .forward() and .backward() enables to save memory

consumption due to that by clearing (erasing) memory of data and

grad when it is not referenced by any subsequent computation. (More

precisely speaking, it doesn’t free memory actually. We use our memory

pool engine by default to avoid memory alloc/free overhead). The

unreferenced buffers can be re-used in subsequent computation. See the

document of Variable for more details. Note that the following

loss.forward(clear_buffer=True) clears data of any intermediate

variables. If you are interested in intermediate variables for some

purposes (e.g. debug, log), you can use the .persistent flag to

prevent clearing buffer of a specific Variable like below.

loss.forward(clear_buffer=True)

print("The prediction `y` is cleared because it's an intermediate variable.")

print(y.d.flatten()[:4]) # to save space show only 4 values

y.persistent = True

loss.forward(clear_buffer=True)

print("The prediction `y` is kept by the persistent flag.")

print(y.d.flatten()[:4]) # to save space show only 4 value

The predictionyis cleared because it's an intermediate variable. [ 2.27279830e-04 6.02164946e-05 5.33679675e-04 2.35557582e-05] The predictionyis kept by the persistent flag. [ 1.0851264 0.87657517 0.79603785 0.40098712]

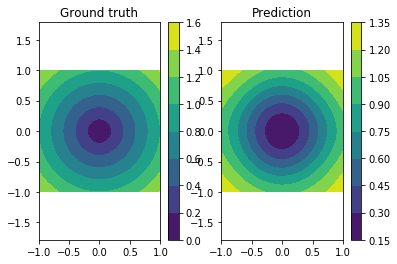

We can confirm the prediction performs fairly well by looking at the following visualization of the ground truth and prediction function.

plt.subplot(121)

plt.title("Ground truth")

plot_true()

plt.subplot(122)

plt.title("Prediction")

plot_prediction()

You can save learned parameters by nnabla.save_parameters and load

by nnabla.load_parameters.

path_param = "param-vector2length.h5"

nn.save_parameters(path_param)

# Remove all once

nn.clear_parameters()

nn.get_parameters()

2017-09-27 14:00:40,544 [nnabla][INFO]: Parameter save (.h5): param-vector2length.h5

OrderedDict()

# Load again

nn.load_parameters(path_param)

print('\n'.join(map(str, nn.get_parameters().items())))

2017-09-27 14:00:40,564 [nnabla][INFO]: Parameter load (<built-in function format>): param-vector2length.h5

('fc0/affine/W', <Variable((2, 4), need_grad=True) at 0x7f576328df48>)

('fc0/affine/b', <Variable((4,), need_grad=True) at 0x7f57245f2868>)

('fc1/affine/W', <Variable((4, 8), need_grad=True) at 0x7f576328def8>)

('fc1/affine/b', <Variable((8,), need_grad=True) at 0x7f5727ee5c78>)

('fc2/affine/W', <Variable((8, 4), need_grad=True) at 0x7f5763297318>)

('fc2/affine/b', <Variable((4,), need_grad=True) at 0x7f5727d29908>)

('fc3/affine/W', <Variable((4, 2), need_grad=True) at 0x7f57632973b8>)

('fc3/affine/b', <Variable((2,), need_grad=True) at 0x7f57632974a8>)

('fc/affine/W', <Variable((2, 1), need_grad=True) at 0x7f57632974f8>)

('fc/affine/b', <Variable((1,), need_grad=True) at 0x7f5763297598>)

Both save and load functions can also be used in a parameter scope.

with nn.parameter_scope('foo'):

nn.load_parameters(path_param)

print('\n'.join(map(str, nn.get_parameters().items())))

2017-09-27 14:00:40,714 [nnabla][INFO]: Parameter load (<built-in function format>): param-vector2length.h5

('fc0/affine/W', <Variable((2, 4), need_grad=True) at 0x7f576328df48>)

('fc0/affine/b', <Variable((4,), need_grad=True) at 0x7f57245f2868>)

('fc1/affine/W', <Variable((4, 8), need_grad=True) at 0x7f576328def8>)

('fc1/affine/b', <Variable((8,), need_grad=True) at 0x7f5727ee5c78>)

('fc2/affine/W', <Variable((8, 4), need_grad=True) at 0x7f5763297318>)

('fc2/affine/b', <Variable((4,), need_grad=True) at 0x7f5727d29908>)

('fc3/affine/W', <Variable((4, 2), need_grad=True) at 0x7f57632973b8>)

('fc3/affine/b', <Variable((2,), need_grad=True) at 0x7f57632974a8>)

('fc/affine/W', <Variable((2, 1), need_grad=True) at 0x7f57632974f8>)

('fc/affine/b', <Variable((1,), need_grad=True) at 0x7f5763297598>)

('foo/fc0/affine/W', <Variable((2, 4), need_grad=True) at 0x7f5763297958>)

('foo/fc0/affine/b', <Variable((4,), need_grad=True) at 0x7f57632978b8>)

('foo/fc1/affine/W', <Variable((4, 8), need_grad=True) at 0x7f572a51ac78>)

('foo/fc1/affine/b', <Variable((8,), need_grad=True) at 0x7f5763297c78>)

('foo/fc2/affine/W', <Variable((8, 4), need_grad=True) at 0x7f5763297a98>)

('foo/fc2/affine/b', <Variable((4,), need_grad=True) at 0x7f5763297d68>)

('foo/fc3/affine/W', <Variable((4, 2), need_grad=True) at 0x7f5763297e08>)

('foo/fc3/affine/b', <Variable((2,), need_grad=True) at 0x7f5763297ea8>)

('foo/fc/affine/W', <Variable((2, 1), need_grad=True) at 0x7f5763297f48>)

('foo/fc/affine/b', <Variable((1,), need_grad=True) at 0x7f5763297cc8>)

!rm {path_param} # Clean ups